Get Ready to Celebrate Nashville Reads with This Primer on Whitehead’s Books

Get Ready to Celebrate Nashville Reads with This Primer on Whitehead’s Books

Every year, Nashville Public Library (NPL) brings our city together to explore some of the best books out there with Nashville Reads. Through group readings, community projects, special programming, and more, Nashvillians from all walks of life unite to discover more about, not just great works of literature, but ourselves and each other.

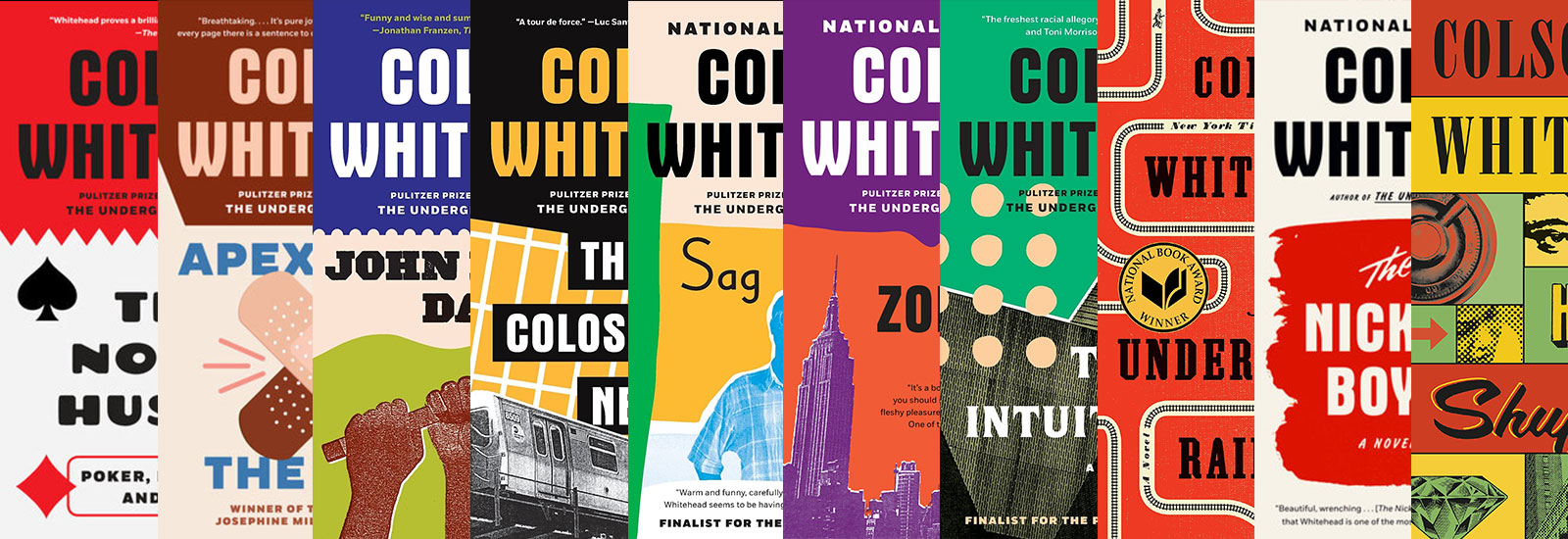

This year, we’re doing things a little differently. While we typically focus on one title for Nashville Reads, this time around we’re inviting you to explore all of the works of Colson Whitehead.

A Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning author — and the recipient of this year’s NPL Literary Award — Whitehead has created a body of work as diverse and immersive as the worlds featured in his books. From stories about failing elevator detectives to a zombie apocalypse to dealing with the lasting effects of institutional abuse, Whitehead doesn’t limit himself to one type of story or one way of telling them.

But with eight masterfully written yet widely different novels spanning more than 20 years, it might be hard to choose where to begin. And so, to introduce you to the wonderful worlds of Whitehead — and help you choose a starting point that’s right for you — we’ll explore some of his most popular books below.

Whitehead’s debut novel burst into the literary world with a unique take on the detective story. Featuring a compelling cast of characters, the book explores the intersection of tradition versus change against the backdrop of a city struggling to adapt to an ever-evolving world.

In an unnamed time, in a city composed of towering skyscrapers, Lila Mae Watson is the first Black, female elevator inspector trained by the Intuitionist school. Her job: ride the city’s many elevators to “intuit” the efficient operation of the elevator and each building’s numerous, interconnected systems. When an elevator that Watson had inspected suffers a catastrophic failure, casting doubt not only on her but the Intuitionist school, Watson must go back to the basics of her education to discover the truth about herself and the terrible circumstances she’s thrown into.

Receiving glowing reviews and solid sales, The Intuitionist launched Whitehead’s literary career. In an interview with Salon, Whitehead, who originally planned for a male protagonist, said of the book, “My whole life I've seen those elevator inspection certificates. I'd go to school, when I was a kid, and come back, and the person had been there, the exact same guy for 10 years. The elevator seemed perfectly fine, so what'd he do? I was thinking about what would make a funny detective story. Well, why not put this person in a situation where he actually has to apply his esoteric skills to a straightforward mystery?”

Writing a follow-up to a debut novel can be a daunting task for any author. Writing a follow-up with completely different characters, setting, and themes is more challenging, still. But Whitehead succeeds in brilliant fashion with John Henry Days.

The book tells the story of J. Sutter, a freelance reporter (and professional moocher) covering the debut of a postage stamp during the first annual festival celebrating the mythic life and legacy of the American folk hero, called “John Henry Days,” in West Virginia. Through his reporting, Sutter (and, by extension, Whitehead), retells the legendary story of John Henry and discovers parallels between the life of America’s “Steel Drivin’ Man,” his own challenging circumstances, and the ways that technology leaves so many people behind even as it elevates others.

Lauded as a triumphant second novel, John Henry Days propelled Whitehead to further acclaim, casting aside any doubts that he was a “one-hit wonder.” On writing the book, Whitehead said to BOMB magazine, “I wanted to break free of my previous novel, The Intuitionist, which is very hermetic; it takes place in one city and has a very small cast. In John Henry Days, a lot of characters present themselves. As I started to think about the transmission of the John Henry myth and the theme of changing technology, I created characters who would provide footholds for discussing the oral ballad transmission, and then sheet music, the advent of vinyl, and then the late 20th century where we have all different technological formats for expression.”

Whitehead has established a reputation for putting unique characters in unique situations, crafting casts and scenarios that are alien to us yet completely relatable. Much of that reputation began with his third novel, Apex Hides the Hurt, a reflection on the power of names and, more importantly, the struggles for power represented in granting something a name.

In the novel, the protagonist, an unnamed “nomenclature consultant,” travels to the fictional town of Winthrop to exercise his oddly unique skill: advising clients about choosing attention-grabbing names for their new products. As the town council considers changing the name of their home, the consultant has to navigate the history and townsfolk of Winthrop, each with their own ideas about what the name should be. Amongst this intricate web of personalities, only one thing is guaranteed: choosing an appropriate name for Winthrop will be an uphill struggle.

Speaking with Alma Books, Whitehead said the motivation for this novel came from an article he read about the process of choosing a name for pharmaceuticals. “... I had a different idea about how we exert [through a similar process] control over certain parts of the city. Like, when someone gets their name on a boulevard: it’s an honor, but as years pass we forget who, say, Roebling is. And I started thinking about how to get these two ideas into a book.”

Turning from the unorthodox, Whitehead’s next novel would tell a more “down to earth,” coming-of-age story, set in a real place and exploring a fictionalized account of his own childhood experiences.

Set during 1985, in the incorporated village of Sag Harbor, New York, the book tells the story of brothers Benji and Reggie Cooper during their summer escapade away from an elite, wealthy, and mostly-White preparatory school in Manhattan. Hilarity ensues as Benji and Reggie reconnect with old friends, immerse themselves in the latest profanities on everyone’s tongues, and interact with a community of close-knit Black families and business owners who have carved out thriving and beautiful lives for themselves.

In writing Sag Harbor, perhaps his most introspective novel to date, Whitehead said said that his goal was to manufacture genuine nostalgia, without leaning on the usual tropes found in many coming-of-age stories. In an interview with Fiction Writers Review, Whitehead said, “... very quickly, I knew that I wasn’t going to have artificial coming-of-age events like a lynching or a big fire or someone accidentally killed. So, I did spend a lot of the time when I wasn’t writing thinking about how to elevate these very mundane moments into the stuff that was art-worthy. I started making notes like, Go to the beach? Get a summer job? And then I had to ask myself: ‘How do these small events eventually become chapters, become compelling points of intrigue for the reader?’“

If Sag Harbor was a pleasant, though compelling, stroll down memory lane for readers, Whitehead’s next novel would be a terrifying vision of a world coming to grips with a near Earth-ending event — a book that would flip established expectations of what Whitehead was capable of as a writer on their heads.

Set in an unspecified amount of time in the future, in a post-apocalyptic America ravaged by a virus that turned much of the world’s population into zombies, Zone One follows three “sweepers” — survivors whose job is to eliminate any remaining zombies — as they patrol across a decimated New York City for three days. As the book progresses, we learn more about their experiences, how they managed to survive, and what they dream of as the world strives to recover.

With Zone One, Whitehead’s goal was to channel his childhood love of authors like Stephen King and Isaac Asmiov as he wrote his own piece of genre fiction — one that could actually stand with the best “true literary works” of the day. Speaking with The Guardian, Whitehead said, “It was those guys who made me want to write in the first place, so it made sense to me that I would eventually do a horror novel, even if it seems strange going from a coming-of-age story like my last novel, Sag Harbor, to a zombie apocalypse. Zombies are a great rhetorical prop to talk about people and paranoia, and they are a good vehicle for my misanthropy.”

Already having established himself as a critical darling in literary circles, Whitehead’s next book would see him enter the mainstream, selling more copies than ever before, taking home both a National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, and seeing his work adapted for film for the very first time.

Set in the Southern United States during the 1800’s, The Underground Railroad follows two Black slaves, Cora and Caesar, as they escape from a Georgia plantation using a fictionalized version of the historic Underground Railroad — one complete with actual railways, railcars, and train stations. Pursued by a slave catcher named Ridgeway, Cora and Caesar must navigate the railroad, with each stop serving as an entry into a unique world filled with intrigue, beauty, and danger.

Initially reluctant to immerse himself in the history of slavery, and the pain inflicted on slaves in 19th century America, Whitehead was finally inspired to tell this story to answer a simple, childhood question. As he related to NPR, “I was pretty reluctant to immerse myself into that history. It took 16 years for me to finish the book. I first had the idea in the year 2000, and I was finishing up a long book called John Henry Days, which had a lot of research. And I was just sort of, you know, getting up from a nap or something (laughter) and thought, ‘You know, what if the Underground Railroad was an actual railroad?’ You know, I think when you're a kid and you first hear about it in school or whatever, you imagine a literal subway beneath the earth. And then you find out that it's not a literal subway, and you get a bit upset. And so the book took off from that childhood notion.”

Coming off the major success of The Underground Railroad, readers and critics alike were anxious to see if Whitehead could make lightning strike twice in such a big way. In typical Whitehead fashion, he did — as only an author like Whitehead can.

The Nickel Boys follows New York businessman Elwood Curtis during two periods in his life. In the modern day, Curtis is drawn into an investigation into the Nickel Academy, a long-closed juvenile reformatory facility in Florida. As the bodies, both literal and figurative, and the awful, hidden history of Nickel Academy come to light, Curtis is forced to confront the trauma of his youth, and the abuse, neglect, and racism he encountered as an attendee at Nickel Academy.

Heralded as a more than worthy follow-up to The Underground Railroad, The Nickel Boys netted Whitehead even further acclaim from readers and critics alike, as well as a second Pulitzer Prize. Inspired by the true story of the Dozier School for Boys, where men and boys were beaten, raped, and murdered for years, Whitehead wanted to write a book that would inspire real change and real action. As he discussed with Vanity Fair, “I didn’t want to do another heavy book. The Underground Railroad took a lot from me. I didn’t want to deal with such depressing material again. But [when former President Donald Trump was elected],I felt compelled to make sense of where we were as a country.”

Whitehead’s latest book, just released in September, is a sweeping crime epic that’s already heralded as one of Whitehead’s greatest works, debuting at #3 on the New York Times Bestseller List.

The book follows Ray Carney, who lives an upstanding, straightforward life as a furniture salesman in Manhattan with his wife, Elizabeth. While Carney’s family was heavily involved in crime, he has resolved to live a decent life, only hustling as a fence for stolen goods to expand his own showroom. But when his cousin, Freddie, volunteers Carney as a fence for a heist that goes terribly wrong, Carney is drawn into the world of crime he’s mostly steered clear of, and must reconcile the criminal, devoted husband, and businessman sides of himself.

Written in small chunks over several years, and finally completed while Whitehead was isolated at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, Harlem Shuffle continues his recurring themes of race, social class, and power. Carney doesn’t really want to be a criminal — he’s just taking the only options he feels he has to rise above his criminal heritage. In relating that experience, Whitehead explained to Vulture that, “I was trying to capture the dynamism of the city. Harlem — before the Great Migration, before the influx of Caribbean immigrants in the ’20s — is a neighborhood of German, Italian, Irish, and Jewish people from all over the Earth. They came to America with nothing, and they entered the middle class and moved away, and then the next group came in. Maybe that’s Black Americans from the South, maybe it’s Black folks from Barbados and the West Indies, like my mom, like my grandmother was. She came through Ellis Island in the ’20s from Barbados. Harlem stays the same, but behind all that, the population in the townhouses, the people who own the streets and the buildings, is always turning. I definitely wanted to capture that. Then, of course, people rise up and down the economic ladder. Carney rises, and the people in Dumas Club have entered into the upper-middle class. It’s precarious because that’s the nature of Black success.”

While we hope this primer gets you excited for Nashville Reads and the works of Colson Whitehead, the reality is that we could never describe the author’s work and philosophy as well as he could. And, fortunately, you’ve got a great opportunity to hear it from Whitehead himself.

On Saturday, November 13, at 10 AM CST, Whitehead will be presenting a public lecture at Martin Luther King Jr. High School, sponsored by the Nashville Public Library Foundation. The event is free and open to the public, and all you need to attend is to register.

So, reserve your seat, pick the book that sounds most interesting to you, and join us as we celebrate one of today’s best authors at NPL!